In early March, while travel still seemed advisable, I embarked on an Alaskan outreach circuit. I began in Utqiagvik (also known as Barrow), home of our Arctic research site. Utqiaġvik is one of the northernmost public communities in the world and is the northernmost city in the United States.

Look at this beautiful view from the plane! I’m about to land in Anchorage, Alaska.

Life in Utqiaġvik

Life is very different for people at this latitude. The cost of living in Utqiaġvik is 58% higher than the national average, and it’s Alaska’s 4th most expensive city. Importing groceries and other necessary supplies is expensive, and these high prices are passed on to the people. A gallon of milk goes for $15 USD and a large tub of tide detergent costs a whopping $70 USD! As a result, local diets depend on sustenance hunting and these hunting practices are an essential cornerstone to the culture and survival of the Inupiaq people.

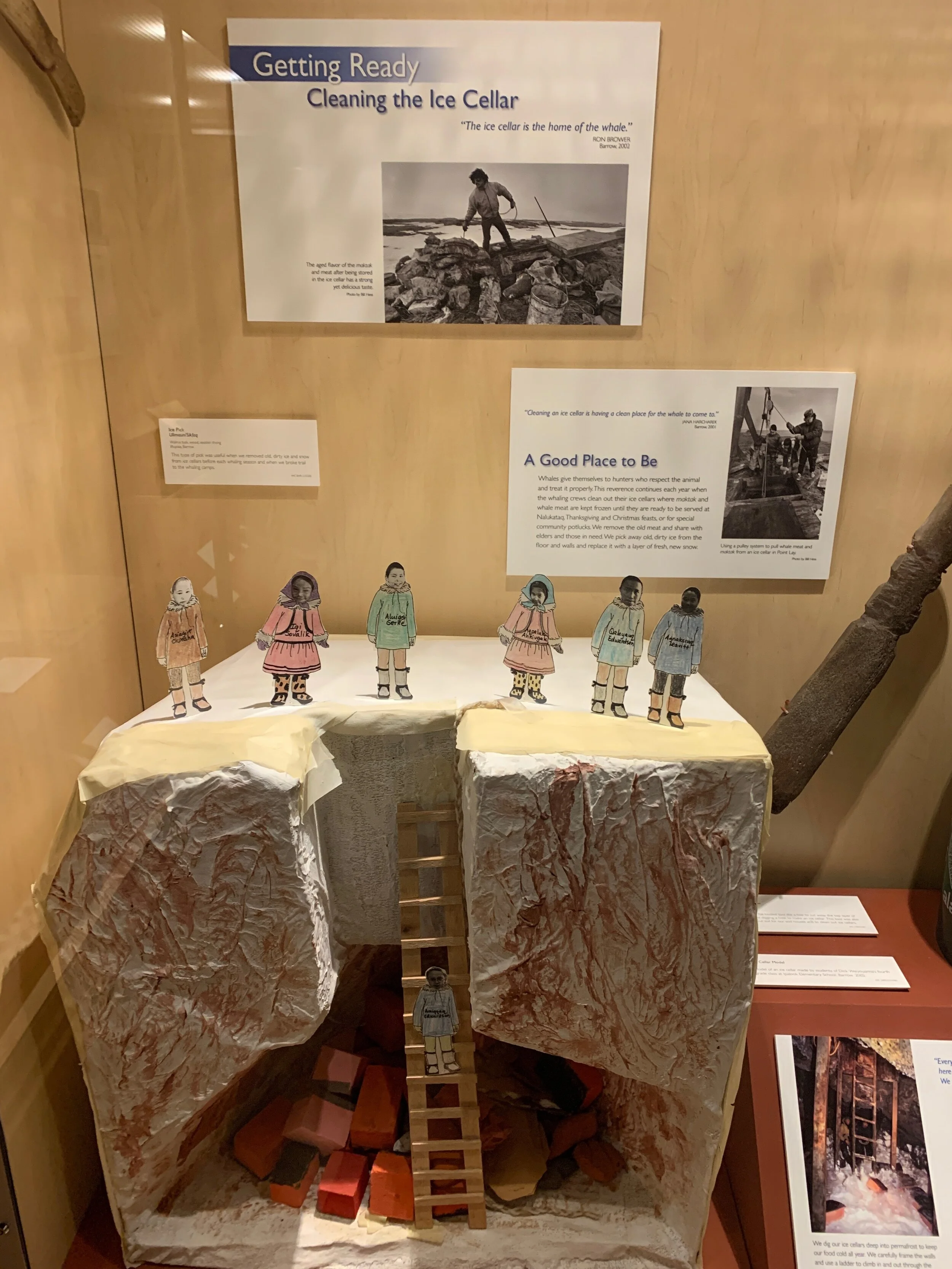

The Iñupiat Heritage Center

This museum houses exhibits and artifact collections — and is a must-visit on everyone’s trip to Utqiaġvik! A large 35-foot replica of a bowhead whale hangs in the center of the building. A whale this size is enough to feed the entire village, twice. And that’s just a medium-sized one!

The hunting, capture, and butcher of whales is a sacred and culturally significant activity that strengthens communities through cooperation, tradition, and of course nourishment from the sea. Unfortunately, these days a whale is not always guaranteed so food security is a major issue in Utqiagvik as is true for many of the communities living in a rapidly changing Arctic.

Constantly Connecting

Getting in touch with people before arriving in Utqiagvik proved to be difficult. I found that the best way to meet anyone was to show up in person. This face-to-face contact is crucial for success in an area where the internet can be unreliable and phones are seldom answered. I did find that everyone I spoke to was helpful and friendly. From the woman who gave me a free ride from the airport, to my visit to the heritage center (where I signed up for an Inupiaq language Rosetta Stone), to the ladies working at Iḷisaġvik College, I was never met with an unfriendly face. I found the general demeanor of the locals to be very warm despite the subzero temperatures.

Although people are generally warm and kind, there are important things to realize when thinking about the people of Utqiagvik, and greater Alaska as well. Local people are constantly bombarded with new scientific projects and outside interest in their resources and land. This constant inflow and outflow of scientists and other professionals along with, all too often, no follow-up once the research is completed, induces a kind of fatigue that makes local people reluctant to meet.

This is why a continuous monitoring of the test site, and continued follow-up outreach, can be so important. No one from afar can understand the complexities of the Arctic without the input of people who actually live there, and it is important to create and maintain these connections, even after testing has finished.

Building trust in relationships takes time and energy, but most importantly it must come from a place of reciprocity and cultural appreciation. Trips like these give Ice911 Research the valuable information needed to not only validate the technology but to increase transparency and constantly improve our outreach process.

I’m underneath a bowhead whalebone. Behind me is the Arctic Ocean. Bowheads have the largest mouth of any animal, which they use to break through the frozen Arctic sea ice.

Welcome to Nome, Alaska!

After several days in Utqiagvik, I said goodbye and hopped on a plane flying almost 17 hours south for the second leg of my trip. I was sent to Nome to investigate a potential place for a future Ice911 field test and to make connections with local community members to find out the best method of outreach.

Land-fast sea ice on the Bering Sea in Nome, Alaska.

Like Utqiagvik, the best way to meet with someone initially is to show up in person. Nome is different from Utqiagvik in the sense that it has a more diverse array of languages and identified tribes. In Utqiagvik, the primary tribal population is Inupiaq and they speak the Inupiaq language. In Nome, however, there are Inupiaq, Central Yupik, and St. Lawerence Yupik, with their respective languages.

Sunsets in Nome, Alaska are breathtaking.

Another difference between Nome and Utquiagvik is the distribution of wealth. In Utqiagvik, although food security will always be dependent on sustenance activities, there is also money from oil and gas industries. There is a state of the art hospital that can airlift people out, an established University, and even an Inpupiaq Rosetta Stone (I signed up for free!).

People flock to Utqiagvik as seasonal workers from all over because they can earn a higher paycheck. Nome does not have the wealth from the oil and gas industry but instead is an old gold mining city. Outside of the downtown area, many villages are in extreme poverty with no running water.

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race

I happened to arrive at a very special time in Nome. It was right before the famous dog sled race called the Iditarod. The word comes from the Ingalik Indian word HaIditarod, which was the name for the river on which the town was built. It means “distant place”.

This is where the famous Iditarod sled dog race ends — Anchorage is the starting line. Sadly, it was canceled this year due to COVID-19.

This annual sled dog event is a re-creation of the famous Serum Run from 1925. This run begins in Anchorage and allowed dogs to bring important medications across 938 miles (1,510 km) by 20 mushers and 150 sled dogs. They made this run in about five days and saved the lives of thousands of people in Nome and the surrounding villages. Nowadays, the race brings forth the best mushers and pups in a celebration to save the sled dog culture and Alaskan huskies, which were being phased out of existence due to the introduction of snowmobiles in Alaska.

Me with my new best friend, Mocha.

COVID hits The North Pole

Unfortunately, Iditarod events were canceled due to the escalating nature of the COVID-19 outbreak.

As the situation escalated, the One Health conference at the University of Alaska Fairbanks was also canceled. One Health was designed to apply collective expertise to solve some of the world’s grand challenges — the integrated health of humans, animals and the environment in which we live. This prompted me to return to San Francisco and to skip Fairbanks altogether.

It’s of critical importance to not bring the virus into Arctic communities. The people of the communities themselves are very resilient, but health care challenges and lack of equipment can make them vulnerable. Now more than ever we need to protect and support Arctic communities and protect the elders who carry insight and wisdom integral to understanding the Arctic.

- Lauren Polash